Millennial Feminism Saved Marriage. So What?

Marriage rates are up and divorce is down. Gen Z may reverse these trends. Should we even care?

One of the less predictable turns my life and my politics have taken is that I — a long-time marriage-skeptical feminist — wound up a woman in my 40s who is not only happily married, but increasingly convinced that marriage is a broad social good worth promoting and investing in. This is not because I think marriage should be the primary organizing mechanism for society or because I think people are missing out if they don’t get married, but because I increasingly believe that the confines of marriage — legal and social — offer human beings incredible opportunities for growth, connection, support, and attempts at something approaching unconditionality. Yoking yourself to another person sounds very romantic at the wedding, but the reality of it is something both more mundane and more transcendent. It is good for society as a whole when we are more connected to each other, when our tightest connections loop into broader networks of intersecting ties, and when those primary connections are firmer and harder to sever. I believe that human apes are meant to live in communities with each other, and that so much about modern life — especially in a place like US — is constructed, socially and physically, to keep us atomized. If decreasing marriage rates meant that people were less often pushed into nuclear family isolation and more often living with sprawling social groups to whom each individual felt deeply tied, I would call that a win. Instead, lower marriage rates have just meant more loneliness. Fewer marriages didn’t free us from nuclear family isolation. They just made more of us more isolated.

That’s changing. After years of decline, marriage rates are up. Divorce rates have continued to nosedive. More American children are being born into two-parent homes. The average age of first marriage in the US is a touch above 28 for women and a touch above 30 for men. With the youngest Millennials turning 30 next year and the oldest in our 40s, that means that this nationwide marriage resurgence is largely thanks to Millennials. And it’s not a coincidence that Millennials are the marriage generation, and also a generation that is more feminist, better educated, and less likely to be incarcerated than those that came before it. Gender equality and individual stability are the keys to getting and staying married. On both counts, Millennials are finally finding our footing.

Which means that things bode less well for Gen Z. And all those right-wing forces radicalizing Gen Z men against feminists and toward either an old-school vision of masculine power or a newer one of unbridled misogyny? They’re the forces driving marriage down. For the Andrew Tates of the world, that’s probably good and fine — misogynist influencers are telling young men to use and abuse women, not to see us as people or attach themselves to us. But conservative and religious anti-feminists do want to see marriage rates increase. They may not realize they’re also perpetuating the very problem they seek to solve.

Most Americans still want to get married. But for marriages to work, we need more egalitarian-minded men.

Conservative marriage researcher Brad Wilcox has a good piece in the Atlantic about marriage’s return. The numbers aren’t extreme, but they’re positive, and the increasing number of new marriages has gone along with shifts toward more equality on the home front. American dads still do far less than American moms, but fathers have more than tripled the amount of time they spend on childcare. Dads now spend 62% as much time as mothers caring for children — in 1965, they did just 25% as much care. And these more-equal marriages are happier ones. Wilcox writes:

In 2022, I worked with YouGov to survey some 2,000 married men and women, asking about their overall marital happiness and how they’d rate their spouse on a range of indicators. The happiest wives in the survey were those who gave their husbands good marks for fairness in the marriage, being attentive to them, providing, and being protective (that is, making them feel safe, physically and otherwise). Specifically, 81 percent of wives age 55 or younger who gave their husbands high marks on at least three of these qualities were very happily married, compared with just 25 percent of wives who gave them high marks on two or fewer. And, in part because most wives were reasonably happy with the job their husband was doing on at least three out of four of these fronts, most wives were very happy with their husband, according to our survey. In fact, we found that more than two-thirds of wives in this age group—and husbands, too—were very happy with their marriage overall.

Feminism is often blamed for increased divorce and decreased marriage, and to a large degree that’s fair. Feminism, I’d argue, has made marriage better, even if it’s made for fewer marriages. Before second-wave feminism, far too many people wound up in marriages that were unhappy or abusive, entered into because of social expectation rather than love or readiness. Patriarchal expectations meant many limitations for women and many entitlements for men. Some marriages were very good. But many weren’t. Many more could have been much better. And this is even more pronounced when it comes to parenting: Imagine how much better off generations of children would have been with dads who were more involved in caregiving and who had more emotional intelligence, and with mothers who had greater independence and more time for self. Feminists have not magically fixed marriage; it remains an institution of profound inequality, and that is only exacerbated if kids come into the picture. But we’ve pushed it in the right direction, even if that means that fewer people enter it.

I suspect that part of why marriage rates have increased is that Millennials have increasingly found professional and financial stability, and Millennial women have found egalitarian-minded men to marry. It’s taken Millennials a while to find our personal and financial footing, and now that we’re better off — we have more savings, more job stability, and higher earnings than we had even a few years ago — more of us are marrying.

It has now been true for many years that marriage and class have gone hand-in-hand, with the college-educated being more likely to marry than the working-class, and more likely to stay married. There are a bunch of reasons for that, including the fact that college-educated people tend to marry later and college-educated men are much more likely than working-class men to be consistently employed, and male unemployment is one of the largest drivers of divorce, marital instability, and not getting married in the first place. There is also the fact that money simply greases the wheels of equality: There is less stress to begin with when you know the rent is going to get paid, and various tension points (house cleaning, childcare) can be partly outsourced to a third, usually female party. But college-educated men are also more liberal than their working-class counterparts. I suspect that means they have more feminist views, and may therefore be more willing to do their share at home, and may therefore be seen as better marriage and parenting material. It also almost surely means, thanks to better employment prospects, that college-educated men are more secure in their role as masculine providers, and don’t find traditional female labor (housework and childcare) to be as much of challenge to their status and masculine identity. All of this — the greater financial stability, the political tendency toward equality, the money to buy equality if you aren’t making it at home — gives a boost to marriages between college-educated people.

Anecdotally, Millennials have also waited longer to get married because we were waiting for the right person. Less pressure to wed meant more choosiness — which means marriage rates that appeared lower for longer, but marriages that are more stable when they do happen.

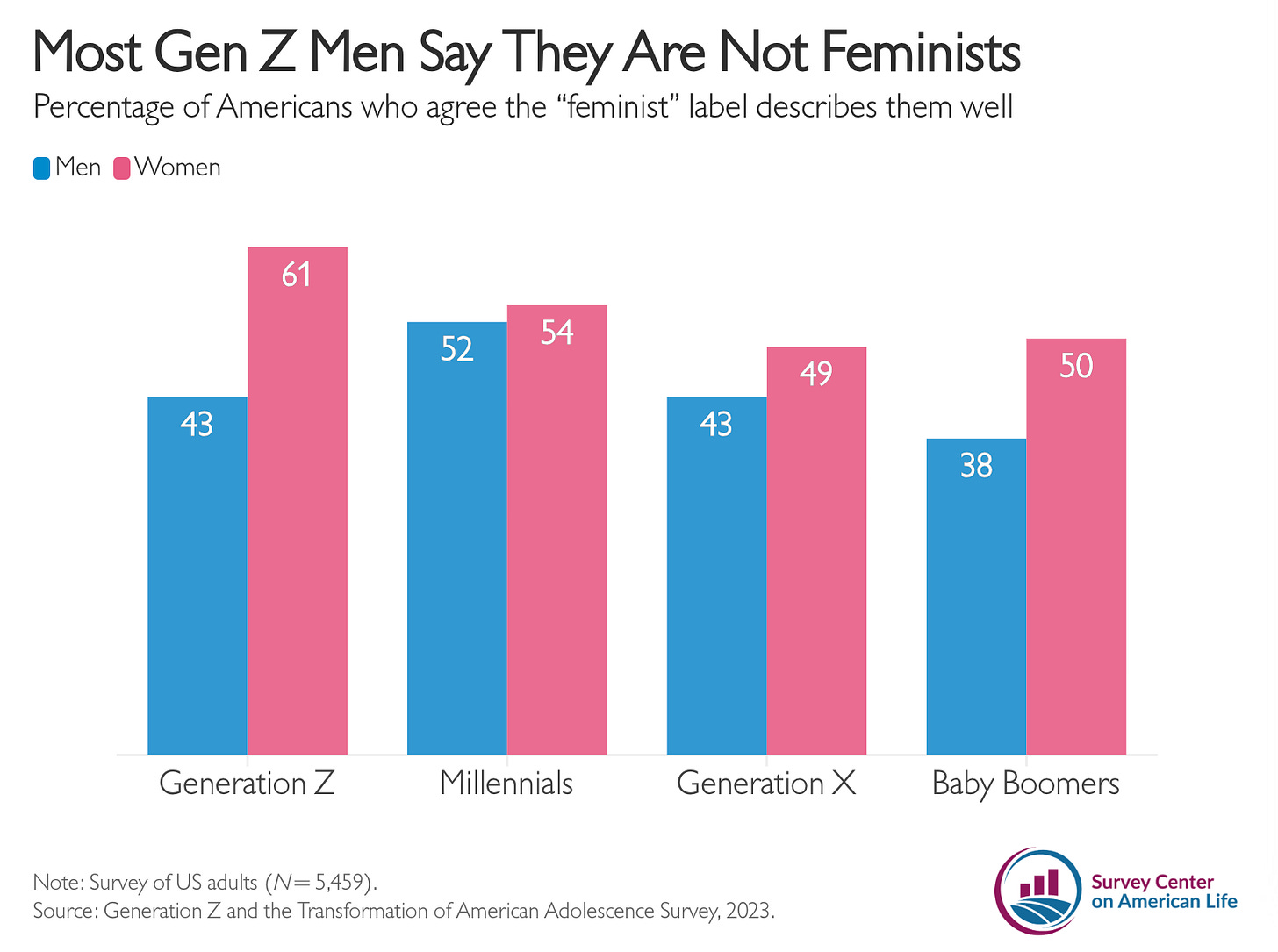

For many Millennial women, “the right person” is a feminist-minded man, even if he doesn’t use the word “feminist.” And Millennial women have more access to feminist-minded men than any generation before or after us. The proportion of Millennial men and women who self-identify as feminists is close to equal: 54% of women and 52% of men. Roughly half of Gen X and Boomer women are feminists, while the men of those generations are largely not. Gen Z women, though, are the most feminist of all, at 61%. But Gen Z men are more in line with the men of Gen X: Just 43% of them say they’re feminists, a nearly 20-point gender gap, the largest of any generation:

I do not know a single heterosexual Millennial couple whose relationship I would say is perfectly gender-equal, and that goes double for those who are parents. But among the heterosexual Millennial couples I’m friends each, nearly every single one tries pretty dam hard to maintain something close to equality. It’s a core relationship value, even if it’s one that isn’t always reached. This sense of fairness and mutual respect is, as Wilcox found, part of what has made Millennial marriages both more numerous and longer-lasting.

There’s also another, less-discussed factor that I believe is at play: fewer of us are behind bars. Millennials are a generation scarred by mass incarceration. Record numbers of us had parents who were in prison, meaning that too many of us were raised in fragile and torn-apart families. A lot of Millennials got caught up in the juvenile justice system, too. But as we hit adulthood, America’s experiment with mass incarceration was tamping down. Crime hit decades-long lows, and the number of people imprisoned went down too. Between 1999 and 2019, the lifetime incarceration risk for Black men was slashed nearly by half. For the Black male Gen Xers born between 1965 and 1969, 22% would go to jail by the time they turned 35, and as Millennials were coming of age, statistics suggested that 1 in 3 Black men would wind up in prison at some point. That turned out to be untrue: The numbers are still dire, but it’s closer to 1 in 5, and still declining. Today, Black men are more likely to get a college degree then go to jail; 20 years ago, the opposite was true. Correlation does not equal causation, but I would guess that there is a relationship between the fact that fewer Black Millennial men are behind bars and the fact that, as Wilcox writes, “the proportion of Black children being raised in a married-parent family rose from 33 percent in 2012 to 39 percent in 2024.”

If you want people to get and stay married, you need to make sure they aren’t locked up, that they have good jobs, and that they approach each other with respect and an aim of egalitarianism.

But then, a question: Why care if people get married at all? Does it even matter if Zoomers largely decide to forgo marriage?

In my ideal world, we would have a variety of legally-recognized family formations. The sense of permanence implied in a marriage doesn’t need to be reserved for the romantic and the sexual. I can see a universe in which best friends decide to take the plunge, and we call it something other than “marriage” but imbue it with similar social respect, and a similar expectation of permanence. Because a goal of permanence is key to making these relationships long-lasting, as is some (reasonable) cost to ending them. It is good that divorce has lost some of its stigma and people can leave abusive or bad marriages, and it’s also good that people generally really want their marriages to last a lifetime, and see some significant but not impermeable impediments to dissolving them.

Excuse me while I get a little bit Yoga Teacher at you, but if you’ve spent time in any wellness-adjacent spaces, you may have heard someone talk about the concept of a “container”: a space with boundaries, within which some magic happens. A yoga class is a container: You are inside of a physical space (a studio), the teacher is telling you how to move your body (a sequence), and from there you experience sensations and emotions and challenges and victories that you almost certainly would not have if you were sitting on your couch, or even if you were moving your body unguided according to your own desires. Within those containers of the class and the sequence and your body itself, you learn things you wouldn’t have: When I move my shoulder like this, it feels like that; I have never felt that muscle before or considered the exact tilt of my pelvis; when I move this way I can unlock that thing and oh wow my body can do this? Maybe you don’t do yoga, but you run and you’ve moved in the container of the training regimen or the race; maybe you don’t exercise but you see a therapist and within the walls of her office different rules apply than those outside and you speak differently and think differently and approach your life from a slightly different vantage point. Many of life’s most transcendent moments involve being pushed by someone else or something else to do something that feels hard, and that’s often achieved because you’re in a space that makes both the pushing and the achievement possible.

Marriage is a container. There are boundaries set by my marriage that didn’t exist in my single life. There are expectations placed upon me, and expectations I place on someone else, things I am asked to do and things I ask for. There is much more joy — being with someone you love, what a gift — but also much more friction, because making a life intertwined with another human being means that sometimes, that other human being pulls on you in uncomfortable ways, or grows in another direction while you’re trying to twine onto them. There is both a deep desire to be known — really, to the core, known — and the knowledge that your partner, no matter how beloved, remains distinct from you, that you will never know every centimeter of their interior, and vice versa. And still: If you’re doing things right, you explore more and more of their landscape, you see how it changes, you notice how it changes you and you change it.

I got into… not a fight, but a conflict I suppose, with a dear friend a few weeks back. It was dumb and I started it, but I think we both felt badly destabilized by the whole thing. And I realized that sense of instability — our fear that a decades-long friendship might fall apart, or might be permanently damaged — came partly from the fact that friendships can be deep and life-changing but there’s no tether of legal requirement or social expectation, no formal proceeding or even final conversation if we’re just not doing this anymore. There is freedom there — I am glad I am not legally tethered to every friend I have ever made. But there is also a lack of unspoken obligation, an instability, a greater sense of vulnerability related to the greater chance that conflicts mean an end rather than normal, surmountable, and often beneficial hurdles. I feel freer in conflicts with my husband than with even my closer friends, because the bedrock assumption of my marriage is that even big disagreements or big annoyances or periods of feeling out of sync are not relationship-enders.

None of which is to say that marriage is better than friendship. It is to say that the obligations and boundaries imposed by marriage have a stabilizing and even freeing effects. We might be collectively better served if we considered how we could formalize and make visible the boundaries, expectations, and obligations of our closest friendships, too. But for now, one of the deepest and most indelible ways we tie ourselves to other people is either being born by them, bearing them, or marrying them.

One of the reasons I decided to get married in the first place was exactly that expectation of permanence. Everyone who has been married a long time tells you that there will be periods of romantic feast and famine, times you are deeply connected and times your ties feel like they’re fraying. I had a hard time picturing a truly awful period with my husband, and I still do. But then and now what appealed was the possibility of whatever lay beyond the hard parts — and doing the work, every day, of showing up for another person. Concepts like friction and discipline aren’t particularly sexy. But when I look at just about every good part of my life, I see friction, discipline, and connection: I see deep relationships that were cultivated with care; I see some effort exerted, even where there is also a lot of ease; and I see intention and the diligence to carry that intention out.

This is not for everyone. There is friction, discipline, and connection to be found in a great many realms, and plenty of ways to grow that don’t involve a wedding. There are plenty of reasons to stay single, and a tremendous amount of fun and freedom to be had. I can imagine a parallel life in which I never married and wow does it look like a good time. There are also plenty of reasons to pair up but not wed, or pair up and split up and pair again. The idea that there is one single way of being in partnership that should work for all or most people on the planet seems frankly insane.

But I also think that a lot of progressives and feminists do things like get married because clearly we think it’s the best decision for us, but never really articulate a case for it Maybe we don’t want to be the Smug Marrieds. We certainly don’t want to be promoting an institution that has historically been so awful for so many women. I personally don’t want to make anyone feel bad — and the reality is that everyone divorced woman I know 100% made the right decision to end her marriage (if it was her choice); most single women I know are doing great, are very socially connected, and have very envious lives (I personally envy many aspects of their lives); and a lot of people want to get married but haven’t found the right person, and it can feel profoundly shitty to have a feminist writer telling them that marriage is so great, why don’t they do it? My actual view on marriage is that it’s great for a lot of people but not everyone and I wish there were a bunch of other relationship formations that were just as socially and legally sanctioned, but that’s not exactly a pithy headline. And so we leave the promotion of marriage to conservatives, who then articulate cases that really don’t resonate with huge numbers of young people, and which may in fact weaken the same institutions they want to preserve.

So. Marriage won’t solve our national loneliness epidemic, but it sure does help. It won’t make everyone happy, and it’s possible that happier people tend to get married, but we do know that on average married people are happier. It won’t fundamentally change who you are, but the practice of living with and tending to a beloved within the container of marriage does shift how you are. People need people, and more people having deep ties to each other is good, which is why I think it’s good that more Millennials are marrying. I also think it’s good that people who don’t want to get married or haven’t found the right person to marry face far less social stigma. I am so, so, so happy I waited until I was in my 30s to marry. But I’m glad I did it. And I hope conservatives who want to promote marriage take a look around and see what’s working — which is more men who see women as equals, and more women with a wealth of life opportunities.

xx Jill

A lovely tribute to marriage. Thank you. I think that it's true that the longer you're in a good marriage, the more you come to value it. Marrying my husband of over three decades was the best thing I ever did, and I love him more now than I did the day I married him. It's true that the older you get, the more grateful you become.

Our 32-year-old son -- a younger Millennial -- is actively wife-shopping right now. He's a highly-skilled trades guy (six years in trades college, three certifications) with a house, shop, truck, two dogs, and a promising new advanced manufacturing business he's getting off the ground. Having been raised by us, he's egalitarian, and knows how to show up for a partner. He's a hair under six feet, blond, cute, smart (though neurospicy), funny, outgoing, easy-going, and has a clear plan for his future that includes being a husband and dad. This should not be hard, right?

But it is. He's kind of in a tough spot because, as a technically working-class guy, he's not that interesting to women with BAs (who are wary that trades guys will tend to want traditionalist relationships, and are usually looking for someone with more equivalent education). Worse: the women he finds online seem to have been badly damaged by growing up in online culture. He calls me after dates with woeful tales: that they want to spend endless money chasing an Instagram appearance standard he finds creepy, or have seriously unhealthy sexual boundaries, or have mental health or substance abuse issues, or are simply angry at men. His dating landscape is a minefield of female trauma -- and he's having a hard time navigating through it to find a partner who's able to bring her whole healthy self to the partnership, and is not liable to blow up the hard-earned stability of his life (which has happened a couple of times already).

I don't know what to tell him. (If anybody has thoughts, please share them.) But your message that Millennials are indeed getting married and mostly getting it right gives me some hope. His older sister has been married for seven years, and they're doing very well. But he's dating mostly Gen Z women in their mid- to late 20s, and he seems to be up against a whole new wave of issues in his dating pool that she didn't have to face.

Thanks for placing the blame for declining marriage rates squarely where it belongs-on the shoulders of misogynist men and religious fundamentalists who view women as appliances designed purely for male convenience.

But you kind of lost me with the container analogy. It kind of sounds like you’re saying “I don’t have to worry about being good and present for my friends any more cos I’ve got my husband and if I’m “dumb” and “start” arguments with him it’s gonna be a lot more inconvenient and expensive for us to split up than it would be to just blow off a long friendship. The problem with letting your friendships slide and deprioritizing them is that if your marriage ever becomes untenable for you (I hope it doesn’t but it most certainly is not invulnerable no matter how great you think it is now) your friendships will not be as supportive for you because you’ve deprioritized them. This is another example of how marriage to men hurts women. It isolates them. And you are encouraging women to isolate themselves in their marriage with this “container” business. I’m more inclined to believe in the “alternative family structures” e.g. women living together romantically or not and helping each other-but if famous journalist that call themselves feminists keep holding marriage to men who are so great (they are doing 20% more at home than their dads did, WOW!) as superior (I guess because it’s what we’ve got right now in the way of a social norm?) those alternative arrangements will be slower to come about.