A Working Mother's Wish List

What actually works to keep families stable, mothers employed, and children thriving.

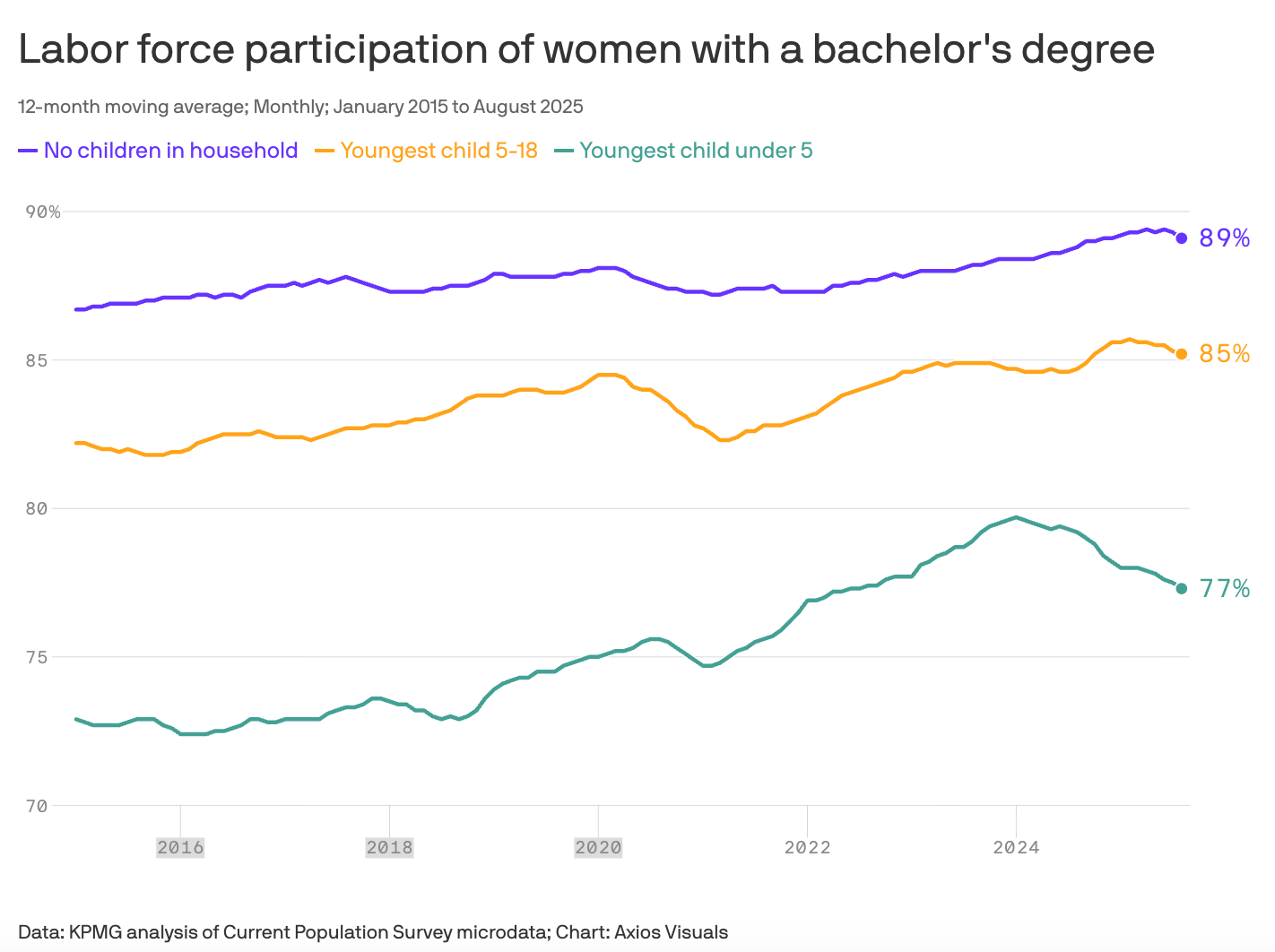

After women’s employment hit an all-time high in the post-Covid era, mothers are now leaving the workforce in startling numbers. There is a yawning gap between college-educated women who don’t have children living with them, and those who have kids who are not yet school age, as this chart from Axios shows:

And these numbers are for college-educated women, who have better employment prospects than women with only a high school education or less. When you look at all mothers with children under six, only 68% of them work for pay. By contrast, 95% of fathers with young children work. And this isn’t just a situation where women are relying on their husbands for support: Even in single-parent households, a quarter of single moms are unemployed, compared to 15% of single dads. Among single mothers of children under six years old, 31% are unemployed; for single fathers of children under six, the unemployment rate is the same — 15% — as single dads more broadly.

Part of the decline in working mothers is just worsening labor market conditions. But the gap between working mothers and working fathers is sticky and persistent.

It’s not that the gap has to get to zero, necessarily. The reality of pregnancy and childbearing is that women bear the physical brunt of it, and need significant recovery time. It a woman is breastfeeding, it’s also a helluva lot easier to be with your baby than pumping in a break room where you may not have adequate privacy or the ability to keep your milk cold. And those early months of infants not sleeping well and requiring round-the-clock care are bleary, fragile ones. The fact that so many American mother go back to work after four or six or even 12 weeks, leaving a teeny-tiny infant in someone else’s care, is among our nation’s most significant failures. The back-to-work date is an inflection point for many women, the moment they decide that their plans to return won’t be realized.

But having mothers out of the workforce for years and years is bad for mothers, bad for families, and bad for kids. Putting aside those fragile first few months, children of working mothers thrive. They have more gender-egalitarian views, with daughters of working mothers doing better in school and making more money as adults, and sons of working mothers being more involved with their own children and more supportive of their working wives when they’re grown. The impact is so great that sons of working moms are more gender-egalitarian than daughters of stay-at-home moms. Both sons and daughters of working mothers wind up better-educated, and a mother working vs. not working has no impact on a child’s happiness.

Working moms are also physically and psychologically better off than moms who don’t work. For mothers of pre-school-aged children, working part time does seem to be a particular sweet spot: Mothers who have part-time jobs actually offer more learning opportunities to their toddlers than stay-at-home moms, and were just as involved in their kids’ schools. Both mothers employed part-time and those employed full-time had lower rates of depressive symptoms and better physical health than stay-at-home moms.

And working mothers are much less likely to wind up impoverished than mothers who don’t work. Despite what tradwife influencers tell you, shit happens. Husbands die, become incapacitated, get sick, serve you with divorce papers. Leaving the workforce entirely means making yourself tremendously financially vulnerable, and reentry is much harder than many women think. Trying to find employment in your mid-50s after two decades of staying home is really, really hard. Skills atrophy; employers don’t want to take someone on who has a track record of opting out. More than a decade ago I left a career as a lawyer to be a writer full-time, and I could not walk back into the Big Law associate role I once had. And frankly that seems fair — I wouldn’t hire me, either.

Simply paying mothers to stay home also doesn’t seem to fix these problems. Finnish researchers looked at a home-care allowance scheme and found that mothers who stayed home but were paid by the state were, unsurprisingly, more likely to stay home longer — and despite the payments saw a long-term negative effect on their finances, probably because when their children were in school or grown, it wasn’t all that easy to simply return to work. And things were worse for kids of mothers who relied on the supplements instead of working: They did worse on cognitive tests, were less likely to attend secondary school, and were more likely to convicted of juvenile crimes.

The American status quo isn’t great for dads, either, who increasingly say they struggle with work-life balance and feel stressed by needing to provide while also wanting to be present parents. American dads really have changed, and they really are much more involved than they used to be. But traditional expectations of breadwinning, and especially the conservative push to have more women relying on a male income, create barriers to fathers’ caregiving, not to mention troubling power dynamics between married couples.

So what works to keep mothers in the workforce, to allow fathers to participate more on the home front, and to give kids the best start possible?

Here’s a wishlist, grounded in research:

1. Nine months to a year of paid parental leave, with pregnancy and recovery set-asides and a use-it-or-lose it chunk for dads.

There is really no question that paid parental leave is one of the most important things for new parents and especially for new babies, but there has been some debate over the ideal amount. Too little and mothers drop out of the workforce because they can’t imagine putting their three-month-old in daycare; too much and women are out of work for two or four or even more years and have a hard time re-entering. A few months is too short (there is good evidence that a child being cared for by a parent for the first four months of life is very beneficial). Two years is too long. The sweet spot seems to be between nine months and one year. At that point, most women have fully recovered. Their kid is hopefully kinda-sorta sleeping and they’ve established a regular schedule and routine. And the baby has progressed beyond that baby-bird super-fragile newborn stage and is physically robust enough that it simply doesn’t feel as scary to leave them with a dedicated caregiver. Finland, it should be said, offers pregnancy leave followed by roughly a year of paid parental leave that can be divided between caregivers, and then high-quality daycare from the time a child is one. The fact that this model has better outcomes for kids and moms than paying mothers to stay home for years should tell us something. An ideal paid leave policy would also be in the Scandinavian mold of setting some of the leave aside for fathers in a use-it-or-lose it model — if dads don’t take it, that leave is just gone. It is incredibly crucial for gender equality (and, I would argue, basic human wellbeing) for fathers to be as involved as mothers in caregiving, but that’s not possible if dad is working full-time while mom is at home. Dads need to be able to stay home too, especially in those first few weeks and months of a new baby’s life, when both parents are getting to know them and learning how to care for them.

2. Childcare subsidies for trained nannies.

Two years ago, I visited a friend and her new baby in Paris. She was heading back to work after several months of paid leave, and after coffee, we met her daughter in the park, where she was being attended-to by her child-minder — of whose hourly rate my friend only paid a fraction. The French government offers a variety of high-quality childcare options, including the famous crèche, but also subsidies for trained, licensed at-home caregivers. Any universal childcare scheme should have this option, which gives parents greater flexibility and more choice, and I imagine is probably preferable for parents of babies under the age of one or two.

3. Universal high-quality affordable childcare.

France also has an incredible universal childcare model, albeit one that is burdened by high demand. Scandinavian countries off this too, and any time I talk to friends who live in these countries, they seem genuinely flummoxed at how Americans do it: How can we work, pay rent, and also pay thousands of dollars in childcare expenses each month? The truth is that many families can’t, and so childcare is a cobbled-together mess of family and neighborhood help and mothers who drop out. And look, it’s wonderful if Grandma can come over every day from 9 to 5 to take care of your baby, or if you can afford a nanny or the kind of daycare that is safe, educationally enriching, and staffed by trained professionals. But a lot of families don’t have those options, and things are especially challenging for the families with the least resources. These less-resourced families are also the ones more likely to rely on family members whose caregiving is frankly not great, or on makeshift unlicensed home-care centers where caregivers have no real training and too often put children at risk. A far better option would be what every more feminist country has already done: Establish a system, not unlike the public school system, of high-quality childcare centers were caregivers are paid well in exchange for reasonable qualifications, that are inspected by the state, and that are subsidized by the state at a sliding scale. This doesn’t just free women up to work, it gives kids a big head start in life with access to child education professionals and people who can help with basic developmental needs from fine motor skills to reading. (When the majority of parents are not reading to their children, we have a problem, and it’s not going to be solved by more mothers staying home). There is a lot of debate about what’s best when it comes to childcare, but this piece sums it up well: “it’s about carers who are sensitive, responsive, and genuinely attuned to the child, taking into account their developmental age, stage, and temperament.” For nearly all families, that will be mom and dad for the first nine months to year of a baby’s life. After that, for some families, a nanny or family member will better fit that role; for others, available family members (including let’s be honest some parents) are not actually all that sensitive, responsive, or attuned, and a child will really benefit from group childcare. Either way, the option of affordable childcare is absolutely crucial for children’s wellbeing and familial stability.

4. More support for part-time work.

“Part-time” feels like kind of a misnomer: When researchers talk about it, they’re including work up to 32 hours per week, which means working a 6.5 hour day on average — to me, that seems like a sensible amount of work, albeit certainly less time than I personally put in. In any event, there is a whole lot of research showing that part-time work essentially allows working mothers to split the difference between household obligations and the benefits of working for pay, and to reap most of the benefits. Children of mothers who work part-time see most of the same benefits in terms of achievement and gender equality as children of mothers who work full-time, while part-time working mothers are just as involved in their children’s schools as stay-at-home moms — and better, on average, at encouraging crucial developmental skills. This makes sense to me, and I see it play out in my own life: I do work full-time but for myself, which means my schedule is wonderfully flexible, so while I do not get to spend as much time with my child as I would like (and I also don’t get to spend as much time on my work as I would like), the time I do spend with my kid is deep, present, and intentional. I am not on my phone. I am not distracted. And I am more efficient at work, too, because there are more demands on my time. It makes sense that women who work part-time have more time to dedicate to their child’s development, but not so much time that they don’t feel pressure to use their time well. There are downsides to part-time work, and they’re obvious: You make less money. But by not totally pulling out of the workforce, part-time working moms are able to re-enter full time more easily once their children are in school, and they’re at least making some money in the years they’re also doing more caregiving. And if a tragedy happens — a husband dies or leaves — they are not totally up a creek, and have many more options for increasing their earnings than women who haven’t worked in years. Supporting part-time work would include more affordable insurance options for part-time workers and requiring employers to offer prorated benefits (paid leave, health insurance, retirement schemes, and so forth). It could also include offering flexible hours and work-at-home options.

5. Shorter commutes and better city living.

I was struck by this piece by Stephanie Murray in the Atlantic about just how bad commuting is for workers generally, and mothers specifically. “A growing body of research suggests that whether a mom can hang on to her job comes down to how long it takes her to get there,” Murray writes. “To help moms work outside the home, society needs to make it easier for them to work near home.” This all means making it easier for families to live in cities, and making sure that cities have good public transport — something most American cities lack. The suburbanization of the American family is bad in about 1,000 different ways, but long car commutes to work is a top reason. It’s wasted time: You can’t get a jump on emails or read a book, and you’re also spending money on childcare while losing time with your child. And people with long car commutes also tend to have longer commutes to do basic errands, adding more wasted time with every trip to the grocery store. Better public transport and more family-friendly cities would go a long way to helping parents work and spend more time with their kids.

6. Enforcement of anti-discrimination laws.

It is illegal to discriminate in employment based on parental status, but we know it happens: That men see a financial bump when they have kids, while women bear financial penalties. We know that mothers face discrimination in employment, whether it’s in being hired in the first place, being paid fairly, or being promoted. Employment discrimination cases like these can be subtle and hard to prove. But government bodies should be looking at large employers’ records — who they employ, who they promote, what they pay — and identifying potentially discriminatory patterns. I imagine that a lot of this discrimination is unconscious, based more in deeply-held assumptions than explicit bias or misogyny (and it seems worth saying that biases against working women are more likely to be held by men who were raised by stay-at-home moms, as well as men with stay-at-home wives). But that doesn’t make it acceptable, and there should be greater efforts taken to identify it and penalize it.

7. Predictable and standard schedules.

For hourly wage-workers, schedule unpredictability and nonstandard working schedules make child-rearing exceptionally difficult. Women working nonstandard schedules tend to be women working low-wage jobs, and women who work the night shift see among the worst outcomes — they’re exhausted, they don’t get adequate time with their children, they miss crucial interactions like bedtime, and they have the hardest time securing high-quality childcare (shift workers are also more likely to be single mothers). Unpredictable working hours — shifts that change by the day or the week — make it impossible for working mothers to plan childcare, which increases family stress, and typically also mean that income is highly variable, which makes family life more stressful still. Children need consistency, and unpredictable work and care arrangements make it impossible to establish the kind of family routine that kids need to feel safe and to thrive. How are people supposed to plan daycare, school pickups, baby-sitter schedules, appointments, and after-school activities if they have no idea when they’ll be working? This kind of unpredictability of course pushes women out of the workplace. Policy-makers could simply require companies to establish consistent hours for employees, even if those hours are part-time, and end the practice of just getting a few days’ or even a single day’s notice for one’s work schedule. Yes, this might be less convenient for employers. But the benefits to employees, children, and society strongly outweigh that inconvenience.

8. Involved partners.

This was supposed to be a policy checklist so I almost left this one off, but it matters who you marry / shack up with / have babies with, and fathers should feel much more of an obligation to do their fair share of parenting and work at home. Caring for their own children and cleaning up their own homes isn’t dads “helping out.” It’s dads doing the bare adult minimum. But there are ways that smart policy could help make this more of a reality. I mentioned this above, but number-one on the “get dads more involved” list would be use-it-or-lose it paternity leave, a few weeks or ideally months of which start from day one of a child’s life. First of all, a postpartum woman needs physical support in the home with a new baby, especially if she has just undergone major abdominal surgery. But just as importantly is the rapid buildup of expertise, especially for first-time parents. If only mom is at home in those fragile first few weeks, then it’s mom who is going to quickly become much more expert at parenting: At diapering and bathing the baby, sure, but also at calming the baby. And when the baby is calmer with mom, well, it just starts to make sense to hand the baby off to mom. This creates a entrenched pattern of mom as expert and child preference for mom, some of which may be natural, but a lot of which is imposed. If dad is home from day one, and if he’s taking on most of the things he can do — doing all or most of the diapering and bathing if mom is the one breastfeeding, for example — and if both parents are sharing in soothing and rocking and playing, dad is going to feel much more expert at parenting, which will pay dividends down the road. I cannot overstate how important those first few weeks are in establishing egalitarian patterns. And yet only about half of new dads take any leave at all when a baby is born — way up from just a few years ago, but still wildly insufficient, especially given that most of those dads are taking a few vacation days, not actual parental leave. The good news is that when fathers have the option of taking paid parental leave, many of them do opt into it, although universally at lower rates than women. Clearly, some sort of carrot-and-stick model is needed here, as well as a big cultural shift. Anecdotally, a lot of men feel stigmatized for taking leave, like they won’t be seen as dedicated workers. We need to flip that: Men who don’t care for their kids should be the ones getting a hard side-eye. Incentivizing men to take paid leave can help.

That’s my wishlist. What would you add to yours?

xx Jill

This feels like a book proposal!

Employers definitely have a bias against those who take time off or pull back for care-taking. My experience after years of working part time while my kids were young, was that prospective employers did not take part time or unpaid work experience seriously. In fact, a number of job applications specify "full time" when asking for job experience. I think keeping my hand in - doing data related technical work - probably did help me obtain full time work when I was ready, but my prospects in terms of opportunities, salary, and job responsibility were quite a bit lower than if I had been performing the very same tasks full time rather than part time.